The full name of Russia’s famous folk choir is the state academic Order of the Red Banner of Labor and Order of People’s Friendship Russian folk choir named after Mitrofan Pyatnitsky. Its emergence was nothing short of a cultural revolution, its subsequent activities glorified Russian folk art.

Beginnings

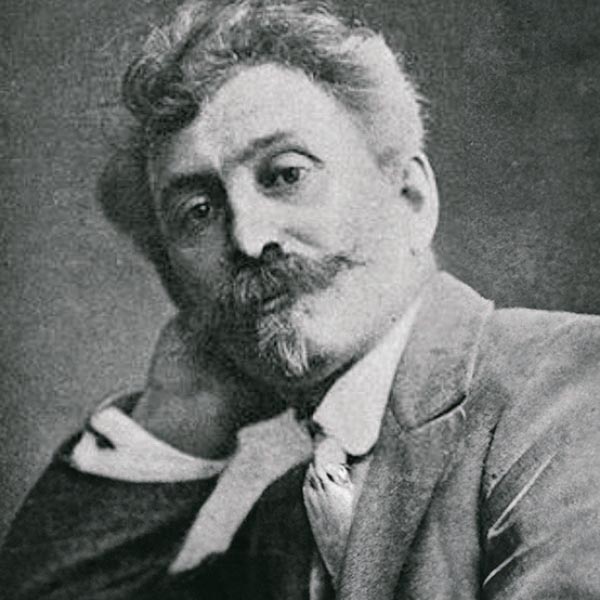

In 1910, Mitrofan Pyatnitsky, a connoisseur of vocal art and a famous collector of Russian folk songs, organized a choir composed of peasants from Voronezh, Ryazan and Smolensk gubernias. The choir was small: the photo taken around that time features the choir master and 14 choir members clad in folk costumes.

The choir’s first performance took place in Moscow on March 2, 1911 and caused a sensation: art connoisseurs were fascinated by the performance of peasants who leapt from ploughing the land to appearing on the stage of the Small Hall of the Nobility Club.

Up to the 1920s, after each concert in the capital the choir members returned to their villages and resumed peasant activities. Eventually, ten years after the establishment of the choir, Pyatnitsky transferred his musicians and singers to Moscow to perform full-time.

The Russian Revolution of 1917 marked the beginning of a new chapter in the history of the peasant choir. On September 22, 1918, Vladimir Lenin attended the choir’s performance in front of the cadets of the first Red Army academy based in the Kremlin. Immediately aware of the choir’s potential, he invited Pyatnitsky to his Kremlin office for a talk and promised to render assistance. The choir’s concert schedule became busier, and after the beginning of regular radio broadcasts in 1924, the ensemble gained national recognition.

Evolvement

After Pyatnitsky’s death in 1927, the company was named after him and the leadership was taken by his nephew, Pyotr Kazmin, a remarkable person and a great connoisseur of Russian folk art.

In 1929, the media launched a campaign under the motto “We don’t need an old choir which sings songs of the kulak village. The new village needs new songs.” The crisis subsided after talented composer Vladimir Zakharov took over the choir and gave it a new artistic direction. He enhanced the choir’s repertoire with his songs imbued with the energy and romantic mood of their time, such as Through the Village, Give Us a Ride on Your Tractor, Petrusha, Green Expanses, etc. The whole country was singing Zakharov’s lyrical songs Who Knows What’s on His Mind, Seeing Off, In the Open.

In 1936, the company celebrated a remarkable achievement: it was awarded the status of a state choir. Two years later, it was enlarged with a dance group under the leadership of Tatiana Ustinova, a distinguished choreographer and a graduate of the Moscow School of Choreography. Tatiana Ustinova studied the folk choreographic language of different regions of Russia and integrated it into her dances. She is the author of the so-called Voronezh step — young women floating like swans in a khorovod. That same year, the company got its own orchestra led by Vasili Khvatov. The talented musician created a unique orchestra composed of bayans, button accordions, horns, zhaleikas, balalaikas, domras, guslas, and rattles, which added color to the choir’s performances and set the mood for songs and dances.

During the Great Patriotic War of 1941–1945, the choir had a busy concert schedule. Together with travelling groups, it entertained the troops on the front lines. The song Oh, my fogs composed in 1943 by Vladimir Zakharov with lyrics by Mikhail Isakovsky gained national popularity and became the hymn of the partisan movement. Live concert broadcasts from the Recoding House studio were immensely popular both on the home front and on the front lines, among soldiers and officers, pilots and sailors. Letters of gratitude streamed from the front in triangular envelopes, the address line indicating simply “For the Pyatnitsky Choir.” One of the surviving letters reads: “We are going into battle, there is a black loud speaker in our shelter playing your songs. Please sing more often… When the last Nazi falls or surrenders, we will stand by your side to celebrate our victory, just as your songs stood by us when we went into battle. Lieutenant Kuvshinov.”

It came true. On May 9, 1945, the Pyatnitsky Choir opened the festivities in honor of the Great Victory on Manezh square in Moscow. The choir members who took part in the concert recalled that after the choir was announced, soldiers who had just returned from the front threw their caps in the air to greet their favorite artists.

In the post-war years, the choir expanded its activities. In the late 1940s, it began touring abroad and visited many European countries. The choir gained international popularity, which, to a great extent, it owed to its leaders who enhanced the choir with their creative output. One of them, Marian Koval, was the choir director from 1957 to 1962. In 1959, the ensemble was awarded the Order of the Red Banner of Labor in recognition of its artistic achievements.

Loud and Proud

In 1962, the company turned a new leaf. Russia’s main folk ensemble was taken over by a new art director, composer Valentin Levashov, who led it for over 20 years. Levashov composed heart-felt, lyrical songs, such as Outside the Village, How Can I Not Love This Land, A Button Accordion Is Singing at the Crossroads, which were among the greatest works of Soviet musical art.

During this period, the choir’s repertoire was enriched with theatrical vocal-choreographic suites and pieces, which reflected cultural and ethnic diversity of Russia (Bryansk Merrymaking, Kaluga Fingerpicking), or spoke about contemporary life (Blossom, the Land of Spring, Hello Volga, A Poem about Moscow). Such musical works required expert grasp of complex polyphony and masterful performance by singers, dancers and musicians.

In 1968, the company was awarded the status of an academic choir and became the crème de la crème of Soviet culture and arts. Its concert geography expanded, its performances were greeted with great enthusiasm in more than 40 countries. “The Russian artists take our hearts in their hands,” the foreign press marveled.

Russian National Choir

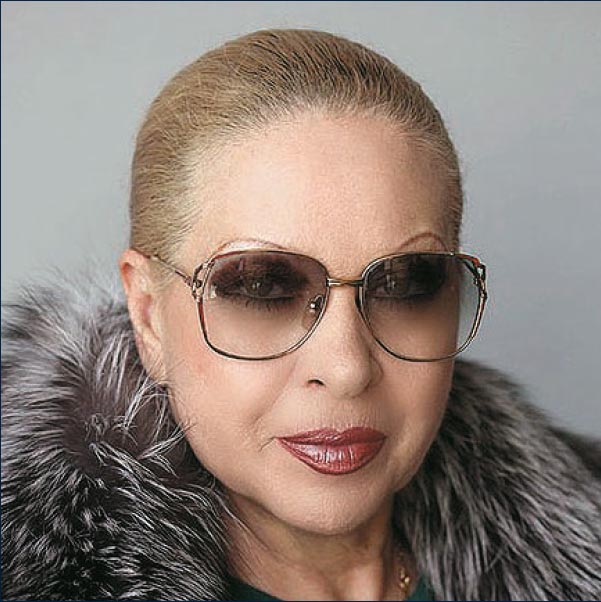

Since 1989, the Pyatnitsky Choir has been led by Alexandra Permyakova. Having been with the choir for many years, she used her talent, uncompromising will and boundless energy to build on the achievements of her predecessors.

Today the choir brings together the best singers, dancers and musicians from 30 regions of Russia, including 40 laureates of national, international and regional performing arts competitions.

The choir’s popularity is unwavering: wherever it goes, it performs to a full house. It is fair to say that the centuries-long common thread of traditional Russian songs links the past, present and future of the peoples of Russia into a single pattern.

Source: pyatnitsky.ru