- Дневник писателя за 1873 год. «Одна из современных фальшей»/ The writer’s diary, 1873. “One of modern hypocrisies”

- Ф.М.Достоевский. Записная тетрадь, 1870–1871 гг. Наброски к «Бесам»/Fyodor Dostoevsky. Workbook, 1870–1871. Ideas for The Possessed.

A writer’s drafts and sketches are not intended for publication. Yet, they can provide answers to the most pressing questions about the author’s life and work. Therefore, the importance of Fyodor Dostoevsky’s drafts and notebooks cannot be overestimated: the most enigmatic writer of the 19th century reveals himself in them in an unexpected way.

Memory of the World

On May 24, 2023, the Executive Board of UNESCO added 64 new collections of documents to the Memory of the World International Register. Among them are Fyodor Dostoevsky’s workbooks presented by the Russian Federation. The documents are held in the Russian State Archive of Literature and Arts and the Russian State Library. Dostoevsky’s manuscripts and notes provide important insights into his biography, philosophical views, creative process, and stories behind his works.

Audrey Azoulay, Director-General of UNESCO, commented on the Executive Board’s decision: “Documentary heritage is the common memory of humanity. It must be protected for research purposes and shared with as many people as possible. It is a fundamental part of our collective history.”

The writer’s archive

Dostoevsky’s wife, Anna Dostoevskaya, was the custodian of his documentary heritage. She kept some of the manuscripts in a safe box at the State Bank and passed the other manuscripts to the Historical Museum where she set up the writer’s museum in one of the rooms. The manuscripts from the safe box were eventually transferred to the Russian State Archive of Literature and Arts. In 1929, the manuscripts held in the Historical Museum were moved to the research department of manuscripts of the Lenin State Library of the USSR. In 1939, the collection expanded to include archival documents from the closed Dostoevsky memorial museum at the Mariinsky Hospital on Bozhedomka Street in Moscow. The collection continued to grow until 1975 through manuscripts donated by private individuals.

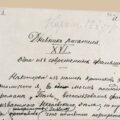

The Russian State Archive of Literature and Arts and the Russian State Library hold 3 notebooks and 16 workbooks of Dostoevsky. The distinction between them was formulated by Soviet literary scholar Vera Nechayeva: “The term ‘notebooks’ refers to three pocket-sized manuscripts with a cover that Dostoevsky carried with him and in which he made brief notes on a variety of topics, sometimes with a pencil on the go, in uneven handwriting. They mainly contain memory joggers and fragmentary notes for his literary works. His workbooks are different. They were intended for work rather than for note-taking. Dostoevsky kept them on his desk (usually in quarto format) and used them for literary pieces he worked on.”

Documents included in the Memo ry of the World Program contain some unique manuscripts. For example, the birth and death records of the Church of the Holy Apostles Peter and Paul of the Stretenye church district. Page 148 contains an entry about the writer’s birth: “On October 30, a baby named Fyodor, the son of regimental surgeon Mikhail Dostoevsky, was born at the hospital for the poor.” The writer’s creed is already evident in his letters from 1841–1843 which mark the very beginning of his creative path. Dostoevsky writes to his brother: “Man is a mystery to be unraveled. If you spend your whole life trying to unravel it, don’t say you wasted your time; I am preoccupied with it because I want to be a human being.”

Calligraphy and graphics

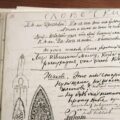

Dostoevsky’s manuscripts are a universe unto itself. They are fascinating in many ways: the evolution of the handwriting, corrections, notes in the margins, the development of plot lines and characters. Moreover, researchers discovered a number of graphic elements in them: faces, oak leaves, finials, calligraphy, and graphic variations on the theme of Gothic arches, lanterns and lancet windows. “Pushkin, while composing, loved to sketch profiles and female legs. Dostoevsky drew Gothic cathedrals,” wrote Dostoevsky scholar Igor Volgin in his book Born in Russia. Dostoevsky graduated from the Main Engineering School that provided the best training in military architecture in Russia. He never lost his passion for architecture.

Calligraphy is yet another expressive element of Dostoevsky’s workbooks. Calligraphic inscriptions can often be found in preparatory materials for Crime and Punishment and especially for The Idiot. and The Possessed. Literary scholar and historian Konstantin Barsht wrote: “In the writer’s arsenal, there are not just many different handwriting styles, often coexisting on the same page, but it is fair to say that Dostoevsky had a distinct handwriting for every thought he expressed, every written word.” Indeed, Dostoevsky’s handwriting varies from illegible scribbles to near-perfect, delicately crafted phrases. Sometimes calligraphic inscriptions are related to the text, and sometimes they exist on their own, as if left on the sidelines as an afterthought.

Dostoevsky drew quite a few portraits in his workbooks. The first sketches appeared in the margins of Notes from a Dead House, and the manuscript of Crime and Punishment contains portraits of Rodion Raskolnikov, Arkady Svidrigailov, Sonya Marmeladova, Porfiry Petrovich, and other characters. There are many drawings in other manuscripts as well The Idiot, The Brothers Karamazov, The Possessed. Researchers still argue about some of them: it is unclear whether Dostoevsky drew the characters or his acquaintances. Perhaps drawing portraits helped him better grasp the character’s personality and get in tune with it.

The visual appearance of Dostoevsky’s drafts and notebooks changed over time: the manuscripts of his early novel Crime and Punishment look noticeably different from the materials for his later novels The Idiot and The Possessed. The writer’s archive can help trace his creative path, but its value goes beyond it. The notebooks filled with uneven handwriting and drawings allow us to catch a glimpse of the inner world of the genius and understand how he conceived and developed ideas that earned him the status of a timeless writer.

Created by UNESCO in 1992, the Memory of the World Program aims to prevent the irrevocable loss and destruction of documents or collections of documents of significant and enduring value, whether on paper, audiovisual, digital or any other support. The program aims to safeguard this heritage and make it more accessible to the general public.

Source: rsl.ru

Photos courtesy of the Russian State Library