In his youth, Boris Pasternak dreamed of becoming a professional musician. He would later give up on this idea, not believing himself to be talented enough. Soon after, he began to take a serious interest in philosophy. Yet his natural talent revealed itself in writing, for which he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1958. However, international recognition would turn into harsh persecution at home.

Choosing a career path

Boris Pasternak was born in Moscow in 1890 to painter Leonid Pasternak and pianist Rosa Kaufman. The future writer grew up surrounded by art. His family often hosted famous guests, including writer Leo Tolstoy, painters Isaak Levitan and Vasily Polenov, and composers Sergei Rachmaninov and Alexander Scriabin. Inspired by Scriabin, young Boris took to music and studied it quite seriously for six years. After graduating with honors from his grammar school, Pasternak decided to prepare for enrollment in the Moscow Conservatory.

It took Pasternak a very long time to determine his future career path. He entered the law department at Moscow State University, but transferred shortly after to the philosophy department.

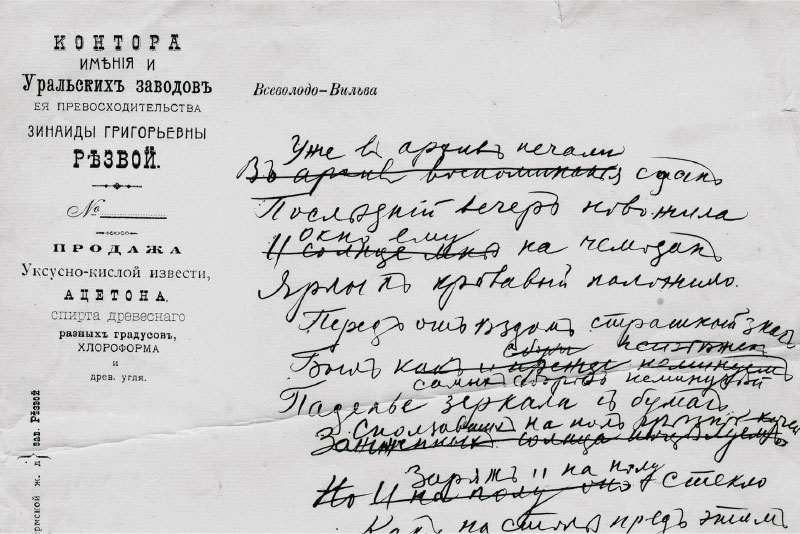

The future writer spent the summer of 1912 in Marburg, studying under Neo-Kantian philosopher Hermann Cohen, who believed that his student would make a brilliant career as a philosopher. However, Pasternak decided to return to Russia, graduating from university with a 1st degree diploma that he never bothered to collect. The diploma is still held in the university’s archives.

The first artistic steps

That same year, Pasternak made his first attempts at writing poetry. He drew inspiration from his trip to Venice and from the rejection of his sweetheart, Ida Wissotzkaya, to whom he had proposed marriage.

Pasternak gradually entered Moscow’s literary circles and became particularly involved in a poetry club of Symbolists, organized by the Musaget publishing house. In 1913, he published his first poem and by the end of that same year he had managed to release a full poetry collection entitled ‘Twin in the Clouds’. This collection would be followed by a second volume, ‘Over the Barriers’, several years later.

Friendship with Vladimir Mayakovsky had a powerful influence over the artistic work and personality of Boris Pasternak. The pair first met in 1914 at a literary gathering, and the acquaintance immediately left huge impression on Pasternak. The rising star of the Futurist movement, self-confident and witty, Mayakovsky simply amazed him. The poet adored Mayakovsky’s early lyrical pieces and, although Pasternak was far from a futurist in his more mature years, his early works contain traces of Futurism that can be largely attributed to the influence of Mayakovsky. The interest was mutual. In the 1920s, Pasternak participated in Mayakovsky’s LEF association of Futurists, but the two poets gradually grew apart. This was partly due to Mayakovsky’s incessant desire for fame — a desire that Pasternak himself did not share. Towards the end of his life, Pasternak would even write the poem ‘It is ugly to be famous.’ Different political views also played an important role in their mutual falling-out.

A somewhat curious piece of Pasternak’s past regards his relationship with Sergei Esenin. The latter resented the works of Boris Pasternak and would eventually spark an open confrontation between the two poets. Their brawl took place at the editorial office of the Krasnaya Nov’ magazine, but the cause of the dispute still remains unknown. Writer Valentin Katayev later provided a humorous account of the fight, giving Pasternak the nickname “mulatto” and calling Esenin the “king’s son”: “… the mulatto, with his genteel ineptitude, tried to punch the king’s son in his cheek-bone with his fist, which he failed to do repeatedly”.

The 1920s was an eventful period in the life of Boris Pasternak. His parents emigrated to Germany, he married artist Еugenia Lourie and had a son, and published a variety of new poetry collections, novels in verse, and poems. Towards the end of the decade, Pasternak published his autobiographical notes, titled ‘Safe Conduct,’ which recounted his youth, his first love, and his trip to Europe.

Soviet rule: recognition and disgrace

In the early 1930s, the works of Boris Pasternak were still recognized by the Soviet government. His collections of poetry were reprinted annually, and he often participated in activities with the Writers’ Union. In 1934, Pasternak even spoke at the first Congress of the Union, where Nikolai Bukharin, editor-in-chief of the Izvestia newspaper, suggested that Pasternak be named the best Soviet poet.

These times brought serious changes within the writer’s personal life. His marriage to Еugenia Lourie came to an end, and the poet later married memoirist Zinaida Neuhaus, with whom he would have a son in 1938. Pasternak and his new wife visited Georgia for the first time. He was amazed by the country and his impressions from this trip would lead to the creation of a series of poems titled ‘Waves’.

In 1935, the poet joined his colleagues on a trip abroad to represent the Writers’ Union at the Anti-Fascist Congress in Paris. Pasternak, who had suffered from insomnia for several months, experienced a nervous breakdown. Researchers of Pasternak’s life attribute the breakdown to his personal disagreements with his second wife, Zinaida Neuhaus.

In 1936, Pasternak published two poems that describe Stalin with great admiration. However, these works did little to improve his spiralling relationship with Soviet authorities. The Kremlin could not forgive his attempts to advocate for the relatives of Anna Akhmatova. Moreover, Pasternak was accused of being separated from reality and possessing a worldview that did not fit the current era. The government expected Pasternak to write poems glorifying the Soviet regime. As a result, Pasternak found himself alienated from official literature.

To support his family, Pasternak began to take on translations. In particular, he translated works from Shakespeare, Goethe, Schiller, Verlaine, and Rilke. The poet treated his translations as standalone works and always tried to accurately convey the message of the source text, preserving the original rhythm and breadth. To this day, Pasternak’s translations are still considered equally as valuable as the originals.

Doctor Zhivago and the Nobel Prize

Pasternak completed his translation of Shakespeare’s Hamlet in 1945 and would spend the next 10 years of his life writing his epic novel, Doctor Zhivago. The novel’s main character was originally based on Zinaida Neuhaus. However, the writer would find himself a new muse in the translator Olga Ivinskaya and his work on the novel began to progress much faster.

The novel was created in sections, which Pasternak would read to his friends upon the completion of each. Ivinskaya was also tasked with handing out printed copies of the manuscript to all of the writer’s acquaintances, as their opinions on the work were extremely important to him.

As soon as the first chapters of Doctor Zhivago were printed, Olga Ivinskaya was arrested and brutally tortured by the police. They demanded to know what the novel would be about and how oppositional it would be. As a result, Olga Ivinskaya was convicted and spent four years in prison.

The writer finished his novel in 1955, but publishing houses in the Soviet Union were reluctant to print it. Publisher Giangiacomo Feltrinelli offered to publish Doctor Zhivago in Italy, and Pasternak agreed. After that, the novel was quickly translated into different languages. The Soviet authorities repeatedly tried to confiscate the manuscript and ban the novel, but nevertheless, it grew more and more popular.

The campaign against Pasternak and his posthumous rehabilitation

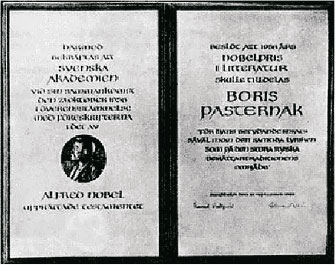

Despite international acclaim, the Soviet government was firmly convinced that Pasternak had only been awarded the Nobel Prize because his novel was considered “anti-Soviet”. The Central Committee of the Communist Party of the USSR even issued a decree, labelling Doctor Zhivago a slanderous work. Pravda newspaper even called Pasternak “a literary weed” (his Russian surname can be translated as ‘parsnip’). Pasternak was expelled from the Writers’ Union, and multiple meetings were held across the country to condemn the work of the “traitorous” writer. Pasternak, unable to bear such smear campaign, wrote a letter to the Nobel Committee and refused the prize.

However, this action changed little back home. Pasternak’s colleagues, with few exceptions, demanded his expulsion from the country. Only the personal appeal of Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru to Nikita Khrushchev was able to save Pasternak, along with a letter drawn up by the KGB which the writer was forced to sign. He stated that he had never intended to harm his country and its people, and had not anticipated that Doctor Zhivago would be perceived as a work against the October Revolution and the Soviet regime.

Pasternak died several years later. In 1987, he was rehabilitated and reinstated in the Writers’ Union. A year later, the magazine Novy Mir published Doctor Zhivago. His refusal of the Nobel Prize was overturned and in 1989 his eldest son received the diploma and the gold medal.

Irina Sheykhetova