Headscarves have long been a popular accessory in Russia. This elegant shawl protects from the cold and the sun, and was worn to complete and complement a woman’s costume. No other headdress gave so much lyricism to a woman’s appearance. In the past, silk Turkish stoles and European lace shawls were always a welcome gift. However, over time, many headscarves began to be made domestically, quickly becoming symbols of Russia.

Printed Pavloposad Shawl

In the middle of the 19th century, Pavlovsky Posad became a center for the production of national headscarves. Printed silk and woolen products from factories near Moscow were being sold out at fairs in no time. Bright, colorful, practical, they immediately became loved by the people. The versatility of the Pavloposad products contributed greatly to their growing popularity: the shawl looked good on everyone. By the beginning of the 20th century, the distinctive Pavloposad products conquered even major international exhibitions. It was the time when the style of the Pavloposad headscarf was finalized. Its distinctive feature was the impeccable harmony in the selection of color combinations and individual decorative elements. The pattern was printed on cream or colored background — black or red for the most part. The ornament included a three-dimensional image of flowers collected in bouquets, garlands or scattered across the field of a shawl. Sometimes flowers were supplemented with thin ornamental stripes or small elements of stylized plant forms. Since the mid-1920s, the traditional floral ornament has received a different interpretation: flowers became larger and more three-dimensional. The colouration of the shawls is based on bright contrasting combinations of red, green, blue and yellow colors.

In the last decade, a lot of work is being done to restore the drawings of old Pavloposad shawls. Along with the development of the classical line, new, modern ornaments appear in accordance with the fashion and style of the time, the color combinations also changes. Like many years ago, the Pavloposad shawl still remains the most popular in Russia.

Orenburg Downy Shawl

The production of shawls out of goat’s soft undercoat originated over two hundred years ago. For the first time products from Orenburg were displayed at an exhibition in Paris in 1857. After that, the shawl gained worldwide fame and recognition.

How can you explain the incredible popularity of these shawls? It’s all about the local breed of goats. Their undercoat is the finest in the world and very durable. Shawls are lightweight, elegant and delicate, but they keep you warm even in severe frosts. It is easy to test their quality. If one passes through a finger ring, then it fully meets the standards.

In the basis of the Orenburg shawl there are silk or cotton threads. The work is incredibly difficult, painstaking and thus takes a lot of time and effort. First of all, the raw material is cleaned of fluff by combing it several times. Then threads are spun on a spindle and the silk “spider web” thread is combined with the downy woolen thread. The yarn is twisted into balls, and then a shawl is knitted or woven. The finished scarf is cleaned again and bleached. One shawl takes from a couple of days to several weeks to complete. Each one has a unique ornament, and therefore the product is unparalleled in the world.

Thick shawls made of gray or white down wool are meant for everyday use. Finer “cobwebs” are worn at festive events. Openwork stoles are suitable for special occasions, they are knitted only by hand and not cheap.

Lace Vologda Shawl

The history of the origin of the craft goes back to the 19th century, when lace-making began to flourish in Vologda and its environs. Samples were brought from all over the world: from France, Holland, Germany, Belgium. The latest fashion trends were embodied by Russian artisans. There emerged a unique method of weaving by means of bobbins, the technique later used for making the famous Vologda lace.

The main decorative feature of the Vologda shawl is its openwork. It is the openwork lattice background, sometimes almost transparent, sometimes with denser, intricate patterns, that allow the light to pass through, making the shawl weightless. Against this background, denser geometric or floral patterns stand out. The contours of the forms are encircled by filigree, a thicker or colored thread that gives relief to the ornament.

Some types of lace have another unusual property: patterns look multidimensional. The ornament is clearly read against the background of the lattice, as if breaking away from it, or as if receding into its depths. The rich play of light and shade is achieved by the varied texture of the threads. There is also Vologda lace without an openwork background — the patterns are woven so densely that color or relief becomes the main expressive means of such a shawl.

Dagestan Gulmendo Shawl

“Gulmendo” in Turkic means “my flower.” Indeed, the main motif of this silk shawl is floral, with rare ornaments of animals, fish and birds. Each pattern was a certain symbol, so the shawl was considered not only an accessory, but also a talisman.

This headdress has a unique history. Iran is considered to be the homeland of Gulmendo, wherefrom samples of headscarves with bright patterns were brought to Azerbaijan several centuries ago. From there Gulmendo came to Dagestan, at the beginning of the 20th century, where it gained incredible popularity. There it became fashionable, and its production was launched. Initially, only men were involved in the manufacture of these unique shawls. Patterns were applied using hand-made stencils. Centimeter by centimeter, the white silk fabric was covered with dye. In order to make the color permanent, the fabric was steamed. While the Azerbaijani kelagays were distinguished by their brightness, the Dagestan gulmendos were more ascetic in color.

Until recently, the art of gulmendo patterned silk headscarves in Dagestan had almost been forgotten. At the beginning of 2000s, the folk handicraft was restored with the preservation of all technological requirements as well as artistic and aesthetic standards.

The headscarves cost from 20 to 35 thousand rubles (about US$ 400–500), because many gulmendos are real works of art, paintings with paradise gardens and intricate labyrinths. They are worn on holidays, given as present at weddings, they are part of traditional costumes and an element of antiquity.

Silk Ossetian Shawl

A silk lace shawl is a significant detail of the Ossetian festive women’s costume. The shawl is called “tsyllae khyz”, which literally means “a mesh of raw silk.” Silk fillet weaving flourished in Ossetia in the late 18th — early 19th centuries, when savvy women began to breed silkworm caterpillars on a large scale. Ossetian needlewomen weaved a mesh using a silk thread, a fillet needle (shuttle) and a stick or flat board. A shawl made in a similar way has spread throughout the Caucasus, for example, among the Chechens it is known as the Ossetian shawl.

Tsillaye khyz differed in shape, which could be triangular, square or rectangular. The size of the mesh and the thickness of the silk thread could also differ. Wedding shawls were of natural light beige color (undyed silk); shawls of black color were also known. The main features of the Ossetian shawls were the folk ornament, embroidered on the mesh, and the type of border processing — lace or fringe.

In Ossetia, the craft of traditional silk shawl making is carefully preserved and passed on by inheritance.

Alena Ischenko

An accessory with meaning

Usually, when talking about the widespread distribution of headscarves and kerchiefs in Russia, one recalls only their exceptional role and a special significance in the Russian national women’s costume. However, kerchiefs were a part of the men’s wardrobe as well. Some kerchiefs made of cotton, wool and silk were produced for memorable dates and important events.

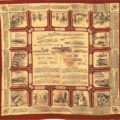

Charter of the Guard Service Kerchief

Made by the factory of the Danilovskaya Manufactory Partnership (Moscow) in the first decade of the 20th century and intended for soldiers to clearly demonstrate the main provisions of the charter and the scheme of the latest weapon of that time — the Berdan rifle.

Millennium of Russia Kerchief

Made in 1862 when Russia was celebrating its millennium. On this occasion, a monument was erected in the kremlin of Veliky Novgorod, which is depicted on the kerchief.

Feat of Ivan Susanin Kerchief

Printed at the Danilovskaya Manufactory in Moscow in 1913 and dedicated to the 300th anniversary of the reign of the Romanov dynasty.