Mikhail Bulgakov was a great Russian writer and playwright. However, many of his books and plays only saw the light of day decades after his death. Although the writer died in poverty, today, Bulgakov’s books are published by the millions, and are actively translated and adapted.

The power of imagination, the talent of the improviser

“Why do you persecute me, fate?! Why wasn’t I born a hundred years ago? Or… a hundred years later. Better yet, if I hadn’t been born at all. Today a guy said to me: “At least you’ll have something to tell your grandchildren”! You are such an idiot”! So begins the story “The Doctor’s Extraordinary Adventures”, which describes Bulgakov’s misadventures in the North Caucasus. He further confesses his aversion to bloody romance: “Since my childhood I’ve hated Fennimore Cooper, Sherlock Holmes, tigers and gun shots…” The difference between the hero and the author is only in one thing — Mikhail never liked medicine.

Mikhail Bulgakov was born in Kiev on May 15, 1891. He was the eldest of seven children of a professor of the Theological Academy and a teacher of a female gymnasium. The parents were musicians, the children sang and all of them were theatergoers.

Young Mikhail’s passion was reading. In 1901 he was enrolled in prestigious First Kiev male grammar school, which was known for its progressive approach: children were encouraged to express their own opinion.

The writer Konstantin Paustovsky, his classmate, recalled: “Bulgakov was full of jokes, fictions, and mystifications. There was an amazing generosity, power of imagination, a talent for improvisation”.

A hundred people a day

Childhood was short-lived. After his father’s death in 1907, the Bulgakov family was in dire straits. Mikhail went to work: he gave lessons, served as a conductor on the railway. In 1909, he entered the medical department of Kiev University, where doctors were well paid.

The First World War caught Mikhail in his fourth year. The medical student tried to enroll in the army, but was deemed unfit for military service. In 1916, having passed his final exams with flying colours, he went to the front as a Red Cross volunteer. But Bulgakov was soon recalled, and appointed to the Nikolskaya Zemstvo Hospital in Smolensk Province.

The former student proved himself well. For a year of work the young doctor received more than 15 thousand patients. Despite his busy schedule, it was at this time Bulgakov began to write stories, the plots of which he took from his professional life.

Subsequently, these works were combined in the cycle “A Country Doctor’s Notebook”: “To me for an appointment … began to go a hundred peasants a day. I stopped eating lunch… returning from the hospital at 9 p.m., I wanted neither to eat, nor to drink, nor to sleep. I wanted nothing, except that no one could come to call me to deliver a baby”.

After returning to Kiev in 1918, Bulgakov opened a private practice. But the revolution interfered with life. The writer was conscripted as a doctor by all the authorities occupying the city. Eventually he ended up in the North Caucasus, in the ranks of the White Volunteer Army, in which his brothers had fought against the Bolsheviks.

The writer sympathised with the White Army, but did not want to fight or practice medicine. He reported for transfer to the reserve on health grounds as soon as possible. When the Whites were defeated, Bulgakov wanted to leave Russia together with the rest of the army, but fell ill with typhus. So he became a Soviet citizen.

Literature is my whole life

Mikhail Bulgakov took up a job as head of the theatre and literature section of the Vladikavkaz Revolutionary Committee. In 1921 Bulgakov found himself in the capital — he walked hundreds of kilometres! He had no money. He worked as a journalist, not lingering anywhere for long, until he got a job at the “Gudok” newspaper. Bulgakov’s feuilletons appeared in every issue. He wrote for the newspaper during the day and created serious works in the evenings.

He devoted himself to literature: “I can’t be anything else, I can be one — a writer. My whole life is in literature. I’ll never go back to medicine again”. “There are only two forces in the world: dollars and literature”, — one of his characters would later say in the play “Zoyka’s Apartment”.

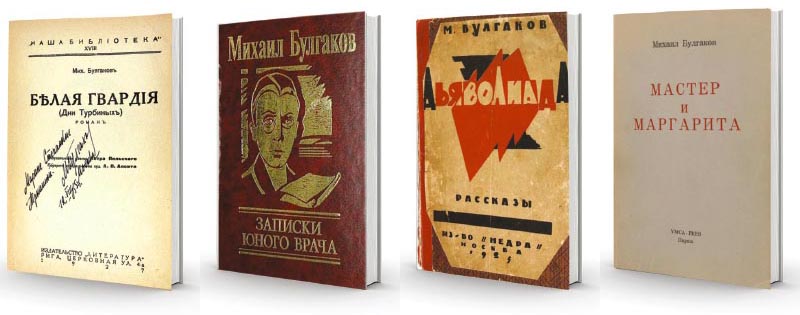

Bulgakov’s first major work was the novel “The White Guard”, which described the life of a large intelligentsia family during the Civil War in Ukraine. The prototypes of the characters were the writer’s relatives and friends. “The White Guard” was enthusiastically received by the public, but displeased both the authorities and the emigrants.

His attitude to the Soviet reality was changing. At first, it was restrained, tidy, and even exploratory (“Let us see and learn, let us be silent”). It seemed to Bulgakov then that it would be possible to live and work normally in the USSR.

In 1925 he, who was already a member of the Writers’ Union, the author of the much acclaimed science-fiction story “The Fatal Eggs”, was offered to write a play based on the novel “The White Guard”. The play, called “The Days of the Turbins”, was performed 13 times in a month, each to a full house. Joseph Stalin liked the play very much and watched it repeatedly.

Soon the relative freedom of creativity in the USSR was overthrown. Mikhail Bulgakov’s plays and prose were banned. Among them was the later famous novel, “ A Dog’s Heart” — the amusing and tragic story of Professor Preobrazhensky, who transformed a stray dog into a rude, illiterate but successful Soviet functionary, Polygraf Sharikov.

I was the one-and-only literary wolf

Mikhail Bulgakov keenly felt the presence of evil. In the summer of 1924 Bulgakov’s novel “Diavoliad”, which mocked Soviet bureaucracy, was published. In the beginning of 1925 he begins gathering material for a novel about the devil (publications of anti-religious magazines, reports of hooliganism by atheists, etc).

Having been driven to despair by money loss, in June 1929 Bulgakov wrote a letter to Stalin asking for permission to leave the country. The writer wrote: “On the broad field of Russian literature in the USSR, I was the only literary wolf. I was advised to dye my skin. This was ridiculous advice. Be it a dyed wolf or a shaved wolf, it does not look like a poodle. I was treated like a wolf. And for some years they chased me according to the rules of literary garden in the fenced yard. I have no malice, but I am very tired …”.

The writer was rejected. A repeated request to the Soviet government had the same fate. But on April 18, 1930, Bulgakov received an unexpected phone call from Stalin himself. And he asked: “Are you fed up with us”? Mikhail hesitated and said: “I have been thinking a lot lately — whether a Russian writer can live outside his homeland. And it seems to me that he can’t”. He will regret that answer all his life… And he will write in his last novel: “Cowardice is the worst vice”.

Stalin ordered to help Bulgakov. He was enrolled as an assistant director in Moscow Art Theater School, which where he was engaged in staging the classics. He tried to put and own plays. And then told his wife, how they were deformed: “Imagine that before your eyes Sergei (Elena Bulgakova’s son from her previous marriage) begins to curl his ears with tongs and says that this is as it should be …”.

At home, the writer continued to work on a novel about the devil, about God, about love, about creativity, life and death — “The Master and Margarita”. He made extracts from theological and philosophical works, encyclopedic dictionaries and holy books. By 1938 the novel was ready, but Bulgakov continued to edit it until his death.

On 10 March 1940 Bulgakov died of a hereditary illness — hypertensive nephrosclerosis. His body was cremated and his ashes buried at Novodevichy Cemetery.

The writer called his last novel a monument to his wife. Monuments to Bulgakov and his characters stand in many cities of the former USSR. He died unrecognized and suffered from non-recognition, but his posthumous fame has outlived him.

Irina Sheikhetova