The 150th anniversary of the famous russian sparkling wine

In November 2020, Abrau-Durso, one of Russia’s oldest wineries, celebrated its 150th anniversary. For one and a half centuries, this winery has been producing legendary Russian champagne of a quality equal to that of the most famous French wines.

First steps

The Caucasian War that lasted half a century ended in the 1860-s, and the north-east coast of the Black sea became part of the new Black Sea District of the Russian Empire. At some point, the head of the district general Dmitry Pilenko noticed a charming location some 25 kilometers from Novorossiysk, with a mountain lake with emerald-green water surrounded by low-rise and arboreous mountain slopes. In 1868, the general addressed the tsar and suggested establishing an estate there that would belong to the Romanov family. In 1870, in order to “put a start to rational agriculture”, Alexander II issued a royal decree to create an estate next to Abrau lake and Durso river, with Dmitry Pilenko as its administrator.

During the first 15 years, Abrau-Durso was run as a multi-purpose farm. They planted orchards there, grew tobacco and hops, kept horses, cows, birds and bees. In 1874, the first vines were planted — 20,000 cuttings of Riesling and Portugieser brought from Europe. The first vintage of grapes was harvested in 1877. But by that time, the enthusiastic administrator Pilenko was gone, and so was his top lieutenant, agronomist Feodor Geiduk, who fell in disgrace. The new administration treated the grape harvest half-heartedly and did not know what to do with it. Then Feodor Geiduk bought up all grapes at his own expense, transported them to his own farm and made 38,5 buckets of wine. In 1882, he sent the first Abrau-Durso wine to Moscow for the XV All-Russia Industrial and Art Exhibitions. Experts appreciated its “stunning values” and awarded a bronze medal to that “rescued brainchild” of Feodor Geiduk.

After such success, new prospects opened for the future of the estate. From that point on, the focus was placed on winemaking, while other spheres were deemed unprofitable. The vineyards began to expand, professional winegrowers were hired, special facilities were built, new equipment was procured, and new staff was added. In just a few years, by 1885, the estate ceased to be loss-making and began to produce decent income from selling still wines.

The history of winemaking in Abrau began with quiet wines, and their production at Abrau-Durso never stopped over the century and a half of its history. It was the birthplace of the famous “Riesling Abrau” and “Cabernet Abrau”, the wines that won international recognition in the 20th century. However, it was the sparkling, not still wines that brought Abrau-Durso its true glory.

Russian Champagne

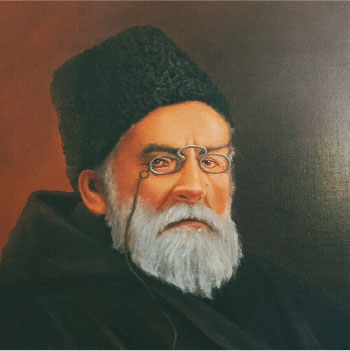

In 1891, Prince Lev Golitsyn was appointed chief winemaker of all royal estates in Crimea and Caucasus. For many years he had been working to create high-quality Russian sparkling wine. In his Crimean estate “Novy Svet”, Lev Golitsyn experimented with different grapes, practiced French production technology, built special tunnels in the mountains for storing and ageing of sparkling grapes. After becoming chief winemaker, he invited a well-known French expert Edouard Robinet. The Frenchman inspected vineyards in the Crimea and northern Black Sea region and made a verdict: if Russia wants to create champagne no worse than the French one, it must do so at Abrau-Durso. The landscape, the climate and the soils of this place, a combination that winemakers call ‘terroir’, reminded of the famous Champagne region. Robinet’s opinion was heard and Abrau-Durso put all efforts in creating sparkling wine. Following the example of the “Novy Svet”, mountain tunnels were built, grapes fit for sparkling wine were planted, and the production technology was being developed.

Prince Lev Golitsyn

In 1897, the Abrau-Durso winery produced its first champagne. Newspapers reported: “The Main Office for Royal Estates brings to the attention that the first royal champagne “Abrau-Durso” is available at royal wine shops in St. Petersburg, Moscow, Odessa, Kharkov, Warsaw and Yalta at a price of 2 roubles 50 kopeck per bottle since January 1, 1898”.

Customers loved the new sparkling wine and the sales were quite impressive: in 1898 alone, 21,500 bottles were sold. Connoisseurs understood that Abrau-Durso brand still trailed the French champagne in terms of quality, but the price was the key: Russian sparkling wine was almost twice cheaper than its foreign counterpart.

The Golden Age

In 1905, at the personal invitation of the Romanov family, a young French winemaker Victor Dravigny arrived at Abrau-Durso. It took him only a few years to shake up the production, to adjust and improve the traditional method of making sparkling wine — and that was an astonishing success. The Abrau champagne equalled the best French wines in terms of quality, became a famous trademark and made its way to the overseas markets of Europe and even America.

Royal wines were always supplied to the cellars of the Romanovs family, but now Abrau-Durso became the only sparkling wine served at the imperial table. The last Russian tsar Nikolai II made the drink a favorite among the Russian aristocracy. As general Anton Denikin once recalled, soon the fancy for Abrau-Durso “spread all across Russia, much to the detriment of French exports”.

The achievements of Victor Dravigny were highly appreciated, even Nikolai II himself honoured the Frenchman with several valuable gifts. When the World War I broke out, all French living in Russia, including the chief champagne maker of Abrau-Durso, were called to the armed forces and went back to their homeland, often leaving their families behind. However, a few months later, Nikolai II personally wrote to the French President Raymond Poincaré asking to allow Victor Dravigny to return to his duties at Abrau-Durso — and the President could not turn down a request from his military ally.

Just before the World War I, Abrau-Durso produced almost half a million bottles of champagne. It was the most profitable and advanced royal winemaking estate in Russia. It was valued at 10 million roubles, had an annual income of over a million roubles, and its prospects at that time looked incredibly bright. Nobody could anticipate that hard times would come for Abrau-Durso as well as for the whole country.

Flagship of Soviet Winemaking

During the revolutions and the Civil War, Abrau-Durso was one of very few enterprises that not just survived, but continued their operations. The employees of the estate worked hard to keep it afloat. They concealed the already-made wine within the tunnels to save it from looters, made deals with all sorts of authorities that existed at that time to supply wine and alcohol to the army, both Red and White. At that tumultuous period, Abrau-Durso even made plans for the future — a monograph about the Abrau region was prepared, and an experimental station was launched, becoming one of the first scientific institutions in the industry.

Victor Dravigny

In 1919, Victor Dravigny and all French specialists that he had invited left Russia for good, but they still managed to teach a large group of champagne makers. These people would become the first Russian specialists in a very rare field and would themselves teach a great number of Soviet experts in sparkling wine.

When the Soviet rule finally established in Novorossiysk in 1920, the Abrau-Durso sovkhoz, or government-run cooperative, was founded. Things were looking up again: while in 1921 the sovkhoz produced only 48,000 bottles of champagne, in 1935 the volume increased to 126,000 bottles. Throughout all these years, Abrau-Durso was the only estate in the Soviet Union that produced sparkling wine.

In July 1936, People’s Commissar of Food Industry Anastas Mikoyan said in his famous speech that “Stakhanovites (top performing workers) now earn a lot of money, engineers and other workers earn a lot, too. And what if they want to buy champagne, will they be able to get it? Champagne is a symbol of material wealth, of prosperity. And we are still producing only 160,000 bottles a year in the whole country, while France produces up to 50 million bottles”.

The government laid out an incredible task for the winemakers — to provide the country with 12 million bottles of sparkling wine by 1942. In other words, they had to increase the production of champagne 100-fold in just six years!

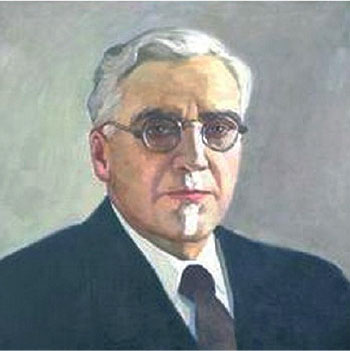

That ambitious goal could only be achieved using a different technology for making of sparkling wine called bulk champagnization. This method was invented in France back in the 19th century, but the Soviet scientist Anton Frolov-Bagreev improved it and implemented in production. He chose Abrau-Durso as a place to begin his experiments, where he succeeded as the chief champagne maker to Victor Dravigny. When using the traditional method, champagnization takes place is bottles and the whole process takes three years. When the method patented by Anton Frolov-Bagreev is applied, champagne is produced in vessels called acratophores over the period of just a few weeks.

Anton Frolov-Bagreev

By 1940, there were already seven plants in the USSR, where champagne was produced in tanks under a single recipe. All sparkling wine was sold under the name “Soviet Champagne” which gradually developed into a brand. But the “Soviet Champagne” made in Abrau became an upmarket wine because it was still manufactured exclusively according to traditional technology.

Before the war, Abrau-Durso sovkhoz became part of the namesake integrated industrial complex. By that time, Abrau-Durso consisted of six state farms and 12 factories. Each division was assigned a specific role and each produced specific wine brands, for example, “Tsimlyanskoye sparkling wine”. The Abrau-Durso itself continued to focus on classical champagne.

After the Great Patriotic War, Abrau-Durso became a division of a powerful production association which again was named after its oldest winery. It incorporated all wine, alcohol and liquor industry of the Krasnodar region. The Abrau-Durso sovkhoz was a model enterprise of the association and a platform for scientific experiments. For instance, it designed a unique brand of export champagne ‘Nazdorovya’ to be sold in the United States.

In 1970, Abrau-Durso reached an important milestone by producing over two million bottles of champagne, in 1984 the production volume exceeded three million, in 1988 — four million. Soviet newspapers reported at that time: “Champagne produced at Abrau-Durso always ranks first among 27 champagne factories of our country in terms of quality”. It was Abrau wines that represented the USSR at international contests, where from 1955 to 2006 they were awarded 200 medals. The “Soviet Champagne” made by Abrau-Durso was exported to more than 30 countries; it was appreciated not only in Europe and the USA, but also in exotic countries such as Brazil, Tunisia, Libya and Indonesia.

Oksana Vasiliadi